In financial markets, startups have long sought to market themselves as "tech firms" hoping investors will value them with tech-company multiples. And often, they do — at least for a while.

Traditional institutions learned this the hard way. Throughout the 2010s, many corporations scrambled to reposition themselves as technology companies. Banks, payment processors and retailers began calling themselves fintechs or data businesses. But few earned the valuation multiples of true tech firms — because the fundamentals rarely matched the narrative.

WeWork was among the most infamous examples: a real estate company dressed up as a tech platform that eventually collapsed under the weight of its own illusion. In financial services, Goldman Sachs launched Marcus in 2016 as a digital-first platform to rival consumer fintechs. Despite early traction, the initiative was scaled back in 2023 after persistent profitability issues.

JPMorgan famously declared itself "a technology company with a banking license," while BBVA and Wells Fargo invested heavily in digital transformation. Yet few of these efforts produced platform-level economics. Today, there's a graveyard of such corporate tech delusions — a clear reminder that no amount of branding can override the structural constraints of capital-intensive or regulated business models.

Crypto is now confronting a similar identity crisis. DeFi protocols want to be valued like Layer 1s. Real-world asset (RWA) dApps are presenting themselves as sovereign networks. Everyone is chasing the Layer 1 "technology premium."

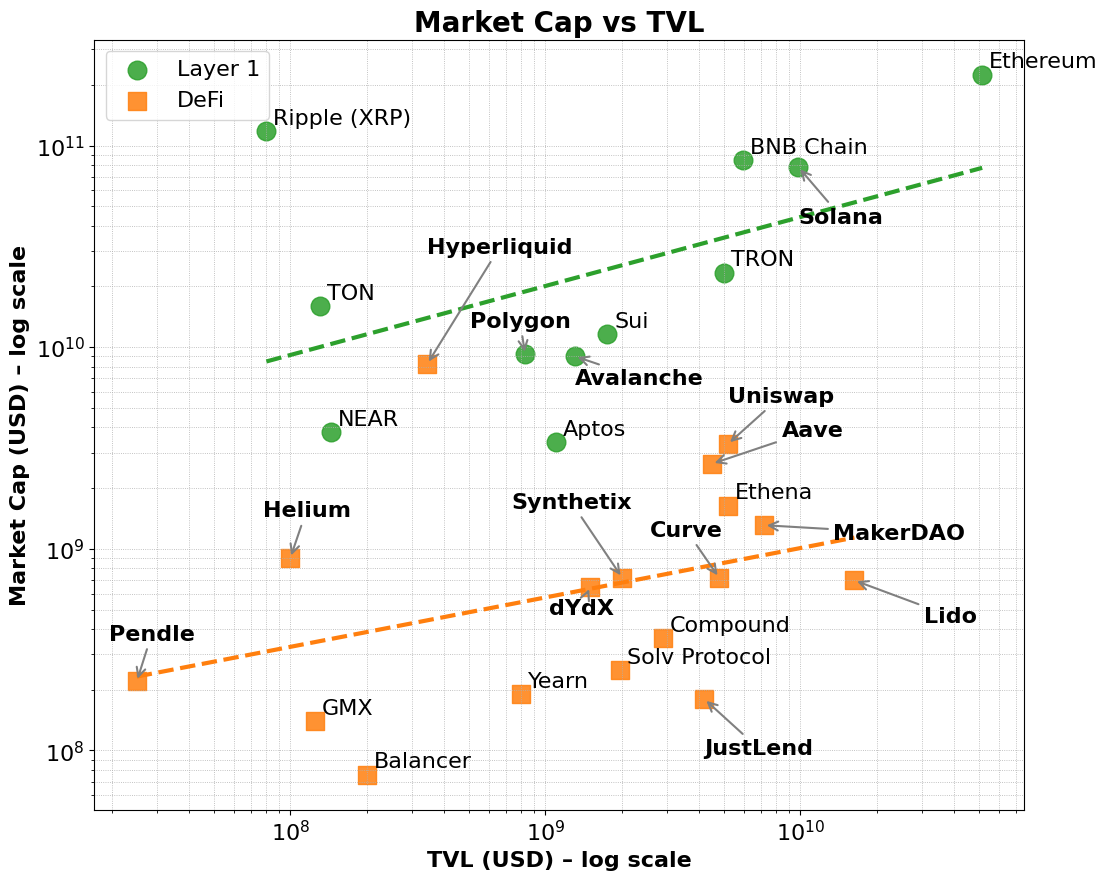

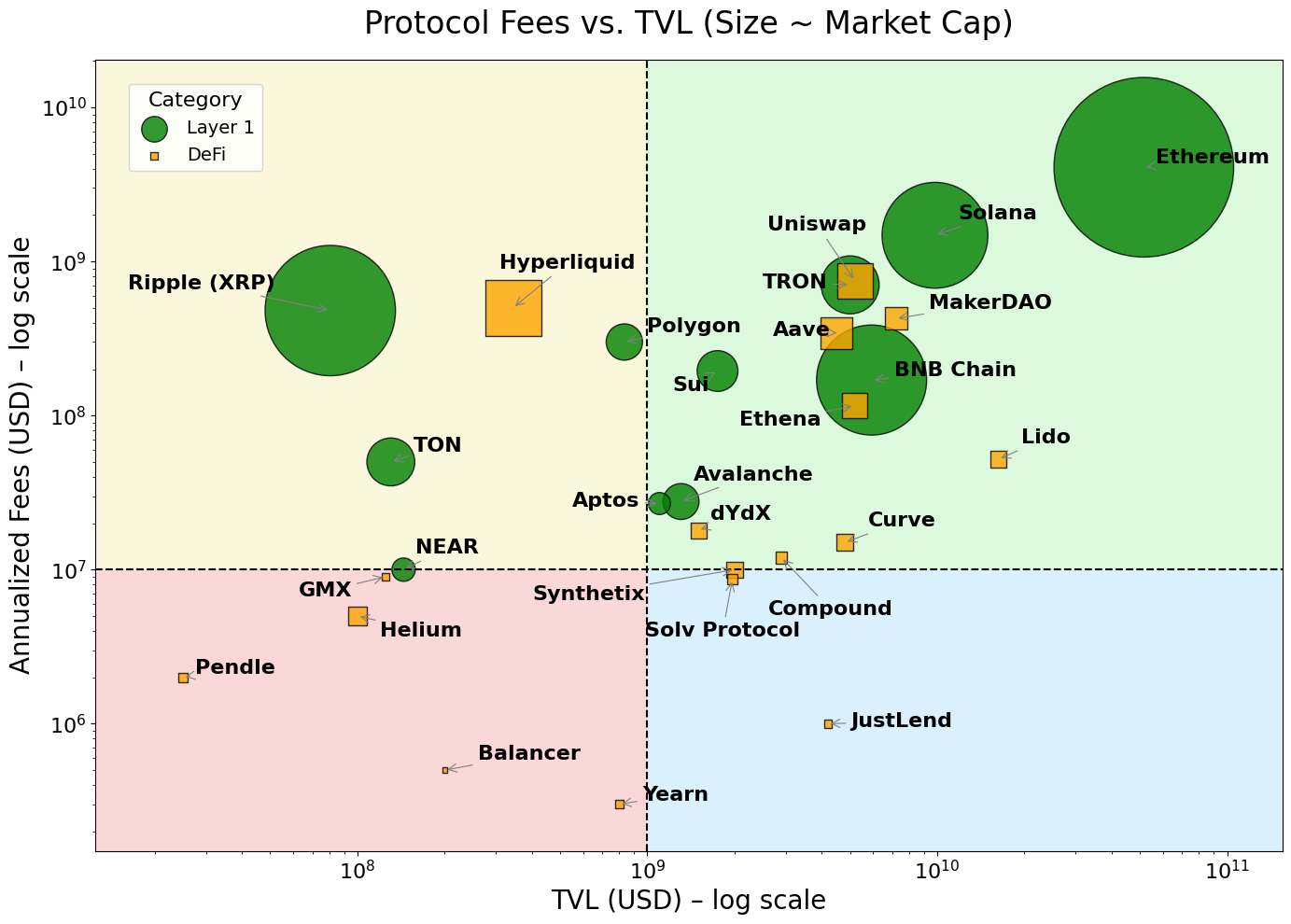

And to be fair — that premium is real. Layer 1 networks like Ethereum, Solana and BNB consistently command higher valuation multiples, relative to metrics like Total Value Locked (TVL) and fee generation. They benefit from a broader market narrative — one that rewards infrastructure over applications, and platforms over products.

This premium holds even when controlling for fundamentals. Many DeFi protocols demonstrate strong TVL or fee generation, yet still struggle to achieve comparable market capitalizations. In contrast, Layer 1s attract early users through validator incentives and native token economics, then expand into developer ecosystems and composable applications.

Ultimately, this premium reflects Layer 1s' capacity for broad native token utility, ecosystem coordination and long-term extensibility. Furthermore, as fee volume grows, these networks often see disproportionate increases in market capitalization — a sign that investors are pricing in not just current usage, but future potential and compounding network effects.

This layered flywheel, moving from infrastructure adoption to ecosystem growth, helps explain why Layer 1s consistently command higher valuations than dApps, even when underlying performance metrics appear similar.

This mirrors how equity markets distinguish platforms from products. Infrastructure companies like AWS, Microsoft Azure, Apple's App Store or Meta's developer ecosystem are more than service providers — they are ecosystems. They enable thousands of developers and businesses to build, scale and interact. Investors assign higher multiples not just for present revenues, but for the potential to support emergent use cases, network effects and economies of scale. By contrast, even highly profitable SaaS tools or niche services rarely attract the same valuation premium — their growth is constrained by limited API composability and narrow utility.

The same pattern is now playing out among large language model (LLM) providers. Most are racing to position themselves not as chatbots, but as foundational infrastructure for AI applications. Everyone wants to be AWS — not Mailchimp.

Layer 1s in crypto follow a similar logic. They're not just blockchains; they're coordination layers for decentralized computation and state synchronization. They support a wide range of composable applications and assets. Their native tokens accrue value through base-layer activity: gas fees, staking, MEV and more. Crucially, these tokens also serve as mechanisms to incentivize developers and users. Layer 1s benefit from self-reinforcing loops — between users, builders, liquidity and token demand — and they support both vertical and horizontal scaling across sectors.

0 Comments